|

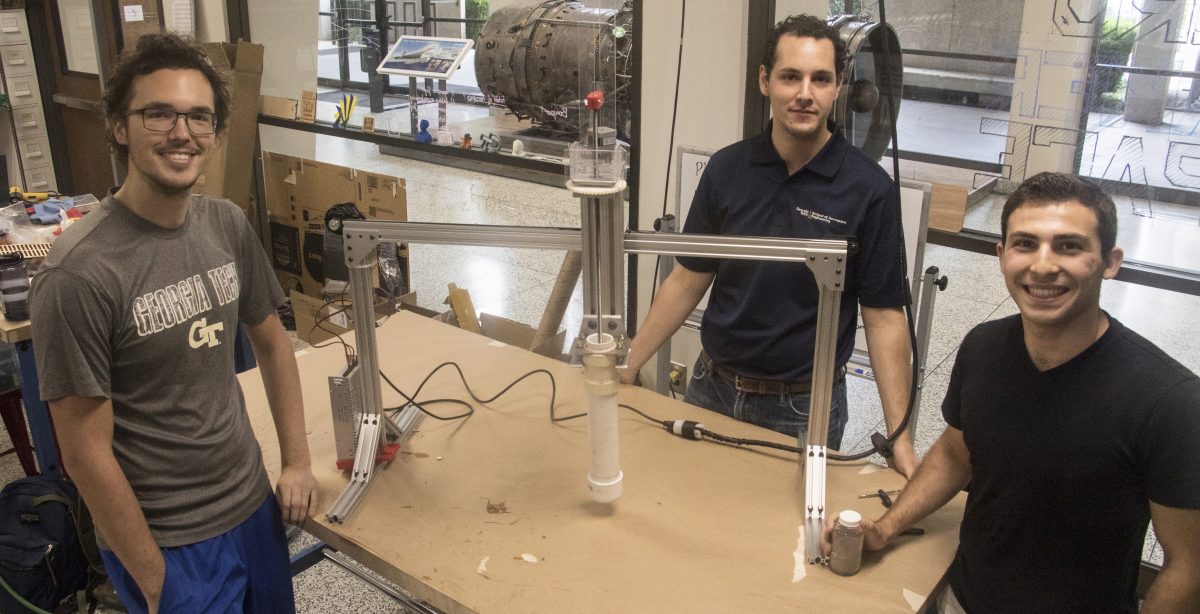

| Time to Make the Concrete. (From left) Samuel Kemp, Prof. Claudio Di Leo, and Nicholas Liccini stand by their Martian concrete 'printer' - designed, assembled, and tested at AE's Aero Maker Space during the summer. |

Ask Nick Liccini what he did on his summer vacation and the answer may exhaust you.

“I took some classes - Differential Equations, Engineering Materials, Statics, Data Structures and Algorithms,” says the 19-year-old Florida native, a rising sophomore at GT-AE. “And I designed and built a test frame for 3D printing concrete on Mars. Using Martian soil. Really.”

(He pulls a jar of dirt out of his backpack.)

“We synthesized this so it has all of the chemical properties of Martian soil. It’s really cool.”

|

| Nicholas Liccini |

Cool, indeed.

Sponsored by a $1,000 Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program grant – and mentored by Prof. Claudio Di Leo – Liccini has been working this summer with two other AE undergrads, Sam Kemp and Allen Boehmig, to design and build a device that can combine the oxide-rich Martian soil with water to create and extrude ferrock, a building material developed by researchers from NASA, GTRI, and IronKast Technologies.

“This is one of my favorite research projects because it brings together engineering, innovation, and pure fun,” says Di Leo. “The best part is that the students really lead the project. My role in this is to enable the students to explore and support that exploration. They do all the work and find out what works and what doesn’t. And I think as you can see they are incredible successful when given that freedom.”

|

| Manufactured 'Martian soil' |

Using iron carbonate as a binder, the team has mixed together, water, and carbon dioxide to create ferrock. The simple 3D printer Liccini and his colleagues built allowed them to test and perfect a formulation of this material which could be suitable for 3D printing. Several chunks were printed and cured this summer.

“It’s strong like the concrete we use on Earth, but it’s actually a little better in one way,” says Kemp of the brownish red slurry they have been manufacturing in the Aero Maker Space over the last two months. “Ferrock absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere. The concrete we use on earth actually emits CO2.”

Liccini nods in agreement with his friend. Ferrock does appear to be an environmentally superior building material - one that future colonizers will no doubt use when they land on the red planet. But what makes this project truly exciting for these up-and-coming engineers is their success in creating a viable system for manufacturing and extruding the ferro-concrete under the harsh conditions that dominate Mars.

|

| Samples of ferro-concrete |

“We created different formulations of the ferro-concrete – using different concentrations of the binder – and we used CAD to design and build a prototype extruder, right here in the Aero Maker Space,” he said.

“We were able to test different samples to see which formulations extruded and cured the best. And I was able to write a program that allowed us to operate the extruder using my computer’s mouse.”

Check out this video of the trio's work in action.

At this point, Liccini stops and looks at his friend. Both he and Kemp know that there’s a lot more to be done before ferro-concrete is a working asset in any Martian colony. Neither of them will let their 'sky-is-the-limit'

ambitions turn them into earthbound blowhards. Not on this project anyway.

Like the scientists who mentor them, the two undergrads calmly outline next steps.

“Because of time, we were only able to attain some qualitative ‘proof-of-concept’ results, rather than producing statistically valid, quantitative results. We need to test more samples, different formulations, and we need to repeat our results,” says Kemp. “But we’ve set this up well. More can be done in the future.”

That may be the most important take-away for Liccini, who initiated the entire project out of pent-up frustration when another engineering class had him spend all semester researching, reading, and studying the concept of additive manufacturing on Mars.

“After all that work, all that reading, no one built a printer to create the ferro-concrete,” he says, throwing up his hands. “So I said: we’re at Georgia Tech. We can do that.”