|

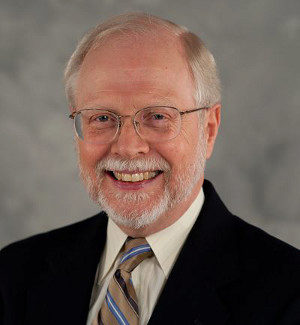

| Prof. Dewey H. Hodges will receive the SDM Award at the SciTech Conference of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in January. |

In January, longtime AE professor Dewey H. Hodges will formally receive the much-coveted SDM Award, a plaudit given by AIAA to the most accomplished researchers in structures, structural dynamics, and materials. That’s an apt description of Hodges, the author of more than 200 journal papers, five textbooks, and numerous named lectureships.

“We’ve always considered ourselves extremely lucky to have lured Dr. Hodges to our School,” says AE chair Dr. Vigor Yang. “The diligence of his scholarship and research have set a high standard for even the most accomplished among his peers on the faculty.”

Don’t expect Dewey Hodges to start echoing that sentiment.

In a profession that often demands singularity of mission, Hodges stands out most notably because he’s a team player who is naturally inclined to understatement.

“I consider myself blessed to have been taught and mentored by people who came before me, truly great minds in this field – people like Earl Dowell, Thomas Kane, Victor Berdichevsky,” he says.

“Really, it is my job to keep propagating, keep expanding the impact of this research through the collaborations I’ve had with my own mentors and with my graduate students. Without robust collaborations, good grief, we’d never get anything solved….”

|

|

"So much of what I've accomplished has been done with some amazing grad students," says Hodges, seen here at the 2013 IFASD conference with "four generations of aeroelasticians": Hodges, his former doctoral student, Prof. Carlos Cesnik, Cesnik's student, Prof. Rafael Palacios-Nieto, and Pallacio-Nieto's grad student Joseba Murua. In January of 2018, a group of Hodges's former students will host Dewey70, a symposium and a planned festschrift in honor of Hodges's 70th birthday year (2018) at the AIAA Sci Tech conference. The three sessions are comprised of 18 papers over a two-day period. |

Hodges’s collaborations are as numerous as they are far-reaching. His work developing variational asymptotic beam sectional (VABS) analysis, a software program, has impacted the development and design of helicopter blades wind turbine blades that are used by numerous aircraft and rotorcraft manufacturers. As the project manager, chief analyst, and co-developer of the General Rotorcraft Aeromechanical Stability Program (GRASP), a hybrid multi-body/variable-order finite element program, he helped to model the complex behavior of bearingless rotor helicopters.

Not surprisingly, Hodges’s resume is liberally sprinkled with career-defining honors (he is a Fellow of AHS, AIAA, ASME, and AAM). But the SDM Award is particularly touching, he says, because it comes from a community of thought leaders and innovators whose work he has followed closely for the last half century.

“I wouldn’t be receiving any award but for the great minds that have surrounded me throughout my career. Divine Providence has placed me on the shoulders of giants with whom I’ve been blessed to interact over the years,” he says.

“Nothing sentimental there. I got something from everyone I worked with.”

This gratitude is a recurring theme with Hodges. You really can’t talk to him about the work he’s done without his giving thanks to his Christian faith – and the many individuals and organizations that have helped him along the way.

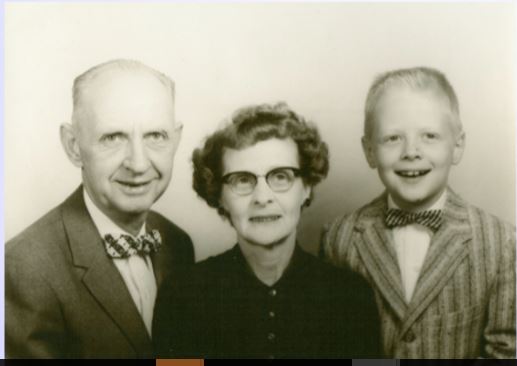

As a child, it was his parents, Plummer and Etha Hodges – rural farmers who cheerfully supported their son’s dream to work “with things that fly.”

“My mother told me that when I was 9, I came in from harvesting barley and I was miserable– covered with sweat, dust, and wasp stings. Apparently, I told her ‘When I grow up, I’m going to work with my mind.’ A few years later, when I traveled 200 miles to go to school at the University of Tennessee, she wasn’t crazy about my leaving, but she never tried to stop me.”

In his tiny high school, it was a guidance counselor named Mrs. June Abernathy, who nudged him to apply for scholarships so he could seriously pursue engineering at an established university. It was an Army ROTC scholarship that allowed him to afford undergraduate school. The Army allowed him to delay his active duty and get a PhD from Stanford under a NASA fellowship that, as he says, “didn’t cost me a nickel.”

At the University of Tennessee, it was his advisor, Mancil W. Milligan.

“The first day of class, Professor Milligan walked in, held up a book and said ‘This is the textbook.’ Then, he put some papers down on a desk and said ‘And this is the syllabus. I’ll see you next time.”

When the class met next, Milligan walked in and said, “’Are there any questions?’”

Hearing none, he continued:

“’Good. Take out a piece of paper and we’ll have a quiz.’”

Hodges laughs as though this happened yesterday.

“He did this every time until we realized that we had to ask questions if we were going to learn. But when we asked those questions, he had the most amazing answers.”

|

|

"My parents, Plummer and Etha Hodges, taught me the old-fashioned work ethic they learned from their parents and I honor them for that," says Hodges seen, here, with his parents during his childhood in rural Tennessee. |

Hodges pauses for a moment and adds:

“And of course, once a week, he’d give us a quiz whether or not we had questions, because that forced us to learn. Indeed, by the end of that term, I felt like I’d really learned something. It was an incredible feeling.”

Milligan and, later, Stanford professor Thomas Kane possessed the two qualities that Hodges has chased for his entire career: exceptional communication skills and an irrepressible passion for the subject. Many of his colleagues and students will tell you he inherited these qualities, too, but Hodges remains in pursuit to this day.

“Kane had a sense of humor that kept you wondering what would come next. He could explain things in a way that was memorable, purposeful. I took every class he taught at Stanford. And every semester that I’ve taught, I have had the goal of rising to his level, as far as quality. It’s still my goal.”

Hodges was moved to follow his mentors into academia, where he would spend the next 30+ years indulging his scientific curiosity and honing his own style of pedagogy. His myriad awards chronicle many of his accomplishments in the former category, but Hodges is always finessing his skills in the latter area.

“I try not to be too influenced by fads. I try to make sure that students don’t feel that it’s sufficient to soak up knowledge in class. I want them to read on their own, too. So, my syllabi usually consist of lecture subjects and reading material as complementary items. I don’t want them to be limited to what the textbook says. There are other places they can look, and I want them to look there….in fact in one class, when I solve the equation on the board, I make a point of solving it differently than what’s in the book.”

Hodges grows quiet at this point. He is not entirely comfortable focusing on himself; he’s even less comfortable with the possibility that he might leave someone out. There’s Dave Peters, Bob Ormiston, a long list of "amazing graduate students," and his wife, Margaret....

“I’ve been very blessed,” he says. “And I’m very grateful.”