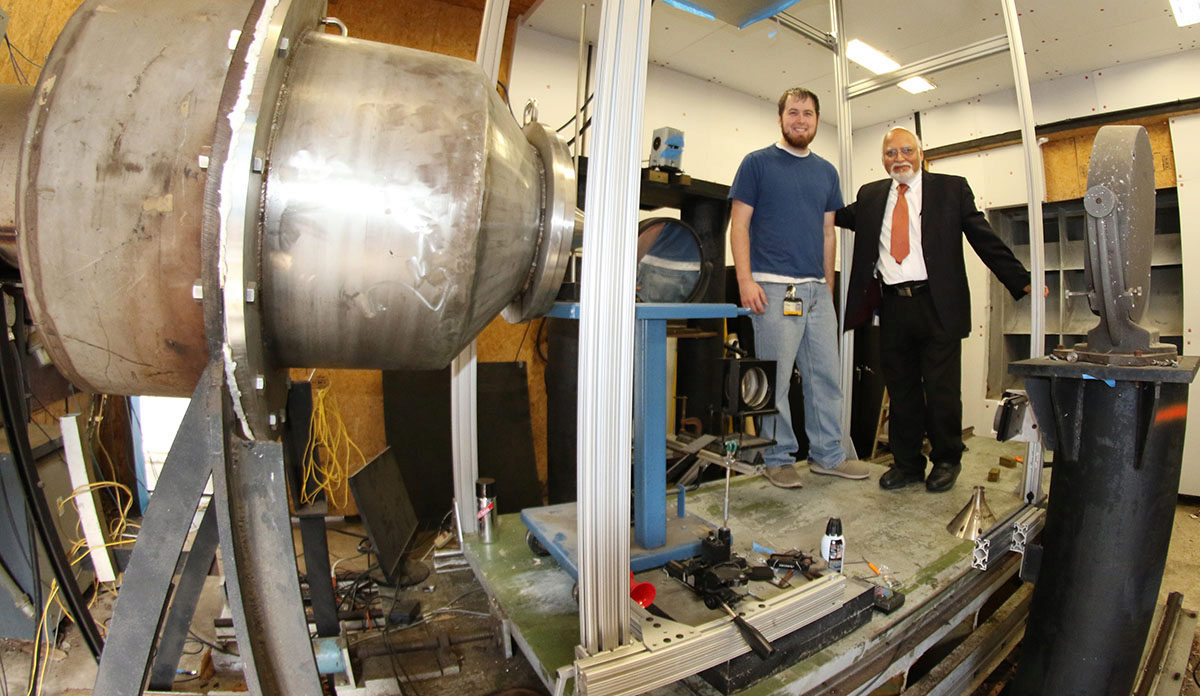

Tracking Sound to Reduce Noise. Newly elected NAE Member Krishan Ahuja is seen here in the Anechoic Flight Simulation Facility where he conducts research designed to reduce jet engine noise.

Tracking Sound to Reduce Noise. Newly elected NAE Member Krishan Ahuja is seen here in the Anechoic Flight Simulation Facility where he conducts research designed to reduce jet engine noise.

As complex as his aeroacoustics research is, Prof. Krish Ahuja espouses an artfully simple philosophy on professional ambition.

Turns out, when Krish Ahuja leaves his lab at Tech, his mind is still whirring. Curiosity still consumes him. Hard work still agitates him.The answer to all of this energy, he says, is to give into it. At least once a week, Ahuja sits down for several hours to plan out art projects. Sculpture. Wood carving. Mosaics. Jewelry. Lately, he's been toying with the idea of picking up oil painting. Once they've been planned out, he's free to pick away at his projects whenever he has a little time. The practice provides a calming contrast to the frenetic pace of his life as a researcher, but, the way Ahuja sees it, it's just another building block in the creative process. The same process that he uses to motivate his research. "As a child, I watched clay sculptors create statues of deities in my neighborhood. In India, I watched jewelers on the street creating jewelry," he explains. "My curiosity for these different things became foundational building blocks for lifelong hobbies. I took a mosaic class two-and-a-half years ago, and I've been creating ever since. But the building block for that interest was the interest I already developed for sculpture. " "Over time, this whole approach - building blocks - expands your view of what's possible. Anything you do can become a building block for the next big thing you pursue. Below: Two of the many artistic creations that are Krish Ahuja's passion when he leaves Tech each day.   |

“Curiosity and hard work,” is how Ahuja sums up a career that recently added National Academy of Engineering Fellow to the list.

“I don’t believe in luck, really, but I guess you could say I've been in the right place at the right time.”

He pauses.

“Still, it’s curiosity and hard work that matter.”

Ahuja is not being coy. A native of Calcutta, India, he has thought a lot about what propelled him to the National Academy -- a career-defining honor. Ever the engineer, he favors the elegance of this two-word answer. But he’s also dead-certain of its accuracy.

You might say he’s done the math.

A self-proclaimed bookworm as a child, he earned money by rising at 4 a.m. to tutor classmates before school. Whenever he had free time, he traveled two hours by bus get to the National Library so he could satisfy his own curiosity. About everything.

“Once I got there, I had to wait a half hour to get a book. And I’d have to read it there and take notes there,” he says laughing. “It was our version of ‘Google’ I guess you’d say. The Encyclopedia Britannica.”

The laughter is as real as the solemnity of his purpose. If he wanted to indulge his ambitions, Ahuja, the fifth of seven children, was only too happy to work for it.

At the Library, he cheerfully dove into books that fed his interest in science. He also developed a love of writing. Both paid off when it came time to pursue higher education. He remembers submitting two essays for a scholarship competition – one on the physics of the moon, the other on space exploration. Neither one was accepted, but his hard work didn't go to waste.

“About a year later, based on my high school mark-sheet [report card], I was invited to take the 36-hour train trip to Delhi to interview for a national scholarship from Rolls Royce for hands-on formal training and education in its aero-engine division. Full five-year scholarship in England. As a part of that interview, they asked me to write an essay. The subject was space exploration, which, thanks to the essay I’d written the year before, I knew something about,” he said.

“I would not be here today if they had asked another question.”

Skipping ahead a few years to the late 80s, Ahuja found himself heading up Lockheed Martin’s aeroacoustics research and serving as the acting manager of its Advanced Flight Sciences Department in the company’s Marietta, Georgia facility. In this capacity, he often worked on projects alongside AE’s best faculty. The work was challenging and life was good. Then Lockheed Martin decided to move its research division to California. Ahuja and his family wanted to remain in Georgia.

Again, hard work paid off.

“I had done well there, so I was able to convince Lockheed to write off this $8 million facility - industry-scale anechoic chambers, high pressure jet flow facilities, and wind tunnels - by donating it to GTRI,” he says. “Then I got GTRI to hire me as a senior faculty research leader with a joint appointment in Georgia Tech's AE School. So that’s why I still have the same office that I’ve had for 30 years. I am very lucky to be still working in this field.”

There's that word 'luck' again. Ahuja quickly refines his take.

"I work hard. I enjoy working hard, researching things thoroughly," he says. "And I'm surrounded by people - at GTRI and the AE School - who give me a lot to do."

That would be an understatement. These days, as a Georgia Tech Regents Researcher, he serves GTRI as the head of its Aerospace and Acoustics Technology Division. In the AE School, as a Regents Professor, he teaches graduate-level courses in aeroacoustics. He is sought-after by government and industry alike for the depth of his research in aircraft noise, acoustics facilities design, flow control, state-of-the-art instrumentation, and advanced signal processing. He oversees a research portfolio that is in the millions of dollars.

"I'm busy, but I don't stress out about any of this," he says. "It just requires that I be thorough, that I work hard. And I am set up to do that quite well, thanks to the wonderful research team and colleagues I get to work with. And a very supportive management both at GTRI and in the AE School is a true blessing."

On a recent tour through his GTRI research facility, Ahuja invited us to explore the Anechoic Flight Simulation facility where one of his many research projects is being conducted. The uniquely insulated chamber is designed to completely absorb sound waves to such a degree that, Ahuja claims, visitors can hear their own hearts beat. What interests him, of course, is its ability to withstand the chaos of hurricane-force winds, a condition that mimics the high-speed cacophony of jet engines.

"There's a problem with jet engine noise, especially on aircraft carriers, where it's so loud it's causing sailors to lose their hearing. So what we're doing in here is we're listening to all the noise produced by the plumes of model-scale engines, determining the locations of sound of various frequencies along the length of the jet using a technique called beamforming, and relating these findings to the flow details of the plumes frequencies that are coming into the chamber," he said.

Ahuja is clearly in his element as he introduces us to the Static Jet Flow facility, the Flow Diagnostic facility and an impedance tube that he describes as "a unique, first-of-its-kind in the world [tool] that can measure the sound damping performance of propellant injectors in a rocket combustor."

More than pride, Ahuja is generating a very serious tone that seems to be moving him out of "interview mode" and into research thinking. Knowing our time is limited, we interrupt to ask him what his next career move might be.

That makes him laugh.

"I am quite happy here, but I have been asked if I ever wanted to go full-time into administration or become a school chair, and I have to say: that would take me away from what I love most," he says. "I am still curious about this field. There is still so much to learn. And I am in the perfect place to do that."