Friends and colleagues of Daniel Schrage are not surprised to hear that his upcoming 'retirement' from the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering is little more than an administrative euphemism. After more than 35 years at Tech, Dan Schrage will not be retiring in the classic sense. On May 15, he will reduce his hours a bit, downsize his office, and prepare himself for a new title - Professor Emeritus. This summer, he'll be

teaching undergrads at AE's Study Abroad program in Ireland. And next fall, he'll return to the AE campus to teach a graduate course with his longtime colleague (and former doctoral student) Dimitri Mavris.

Retirement, for Daniel Schrage, simply means he'll have more time to address another nagging ambition.

"I want to write a book about what I've been doing for the last 50 years - as an active duty military, an engineering faculty at a major technical university, and as someone who's been involved in the development of most of the aviation weapon systems used by today's Army," he said recently, as plowed through mountains of paper in his Guggenheim Building office. "But I just haven't had the time."

No surprise there.

For the better part of four decades, Dan Schrage has spread his prodigious talents between roles as a sought-after professor/researcher in the Daniel Guggenheim School and as the director of Georgia Tech's Vertical Lift Research Center of Excellence, a consortium of government, academic, and industry leaders committed to advancing rotorcraft technology. All of this came after he'd established himself as a powerhouse in two prior careers -- as a decorated Army officer in the Vietnam war, and as an engineer, manager, and senior executive in the Aviation Research and Development Command. His career is punctuated with achievements that would make a lesser man pause - piloting recovery missions over some of the most treacherous battlefields in Vietnam, mentoring more than 50 doctoral (&150+ masters) students, and developing technology that greatly advanced the field of rotorcraft flight. But Dan Schrage is itching to write a book.

In the meantime, we asked him to reflect on some of the experiences that put some gas in his tank over the years. Here are five things he agreed to share.

1. Never give up on a goal you really want to achieve.

"Growing up in rural Illinois, I used to watch a television show about two cadets who had a Corvette that they drove on Route 66. I guess some guys would have been drawn to the car, but I kept thinking it would be cool to be a cadet and study engineering at West Point. It wasn't unrealistic from an academic standpoint - I did well in math and science. So I got recommendations and put in an application. I was selected as first-alternate, which means someone else would have to decline for me to get a spot. My luck - the other guy decided to go."

Schrage doesn't even wince at this memory. It was just a hiccup:

"My parents - both teachers - couldn't afford to send me to my other choice, Notre Dame, so I went to a small school near my home, Quincy College - now Quincy University - where I immediately lettered in basketball and baseball. Now everyone around me was studying phys-ed, and that would have been an easy choice for me to make. My coaches loved me. But I still wanted to be an engineer. And I still wanted to go to West Point. There was no reason I couldn't apply again -- I was still doing well in math and science. So I applied again, this time with the support of coaches who wrote letters telling West Point admissions that they would be sorry to lose me, that I could do academics and sports. The second time, I got in."

2. Make the most of the position you are in (even if it's not your first choice).

"When I was playing basketball at West Point, I wasn't bad at scoring. In fact I was leading for a couple years. But in the system that [Coach] Bobby Knight set up, everyone had their assignment, and he wanted me to play defense and rebound. I think he saw that I was a hard-nosed player, willing to take some roughing up to get the job done. I wasn't afraid to go after the ball. Now I might have started out liking to score, but, under Bobby Knight's direction, I started to love guarding the other team's best players. I was kind of proud of what I got sent in to do. And, looking back, it was fun. I guarded five All-American players - including BIll Bradley, Dave Bing, and Wes Unseld. "

Schrage laughs.

"Unseld, in particular, was tough: 6'8", 280 pounds to my 6'3", 180. That was tough."

3. Never let the heat of the moment prevail. You will get much more from being loyal.

"Playing basketball under Bobby Knight was tough because Bobby Knight was tough. He liked to win and he had a temper. I can remember coming

back from a road trip around midnight, after we didn't win, and he brought us straight to the gym so we could work on our game for a couple of hours before we went to bed. No one said a word. I think we all had sort of a love-hate relationship with him during those years, but loyalty always kept us in line."

"One time, we had just been beaten by his alma mater, Ohio State. It was a tough defeat -- just one point, at the buzzer -- and you could tell it took a lot out of him. Now, after each game, all the players used to wait in the locker room to get de-briefed by Bobby before we went to the showers. It was a show of respect. That night, Bobby was so upset that he didn't show up to the locker room for an hour and a half. None of us showered. We all waited. We owed that to him. When he did show up, he let the assistant coach de-brief us -- he was that upset."

"Twenty years later, when I was at Tech, some people were urging me to consider putting in to be the chair of the school. It was nothing that I seriously considered, but, the next thing I knew, Bobby Knight had called up the dean of the College of Engineering to tell him what a great leader I was, how he should consider me for the job. Never asked him to do it, but I probably couldn't have stopped him if I'd tried. That's the kind of loyalty he had for his players, and, you know, it's not something I've forgotten. I'll be visiting him next month, along with some of the other former players. His health is not great, but our memories are."

4. Teams are only as strong as their least-trained member. Know your team.

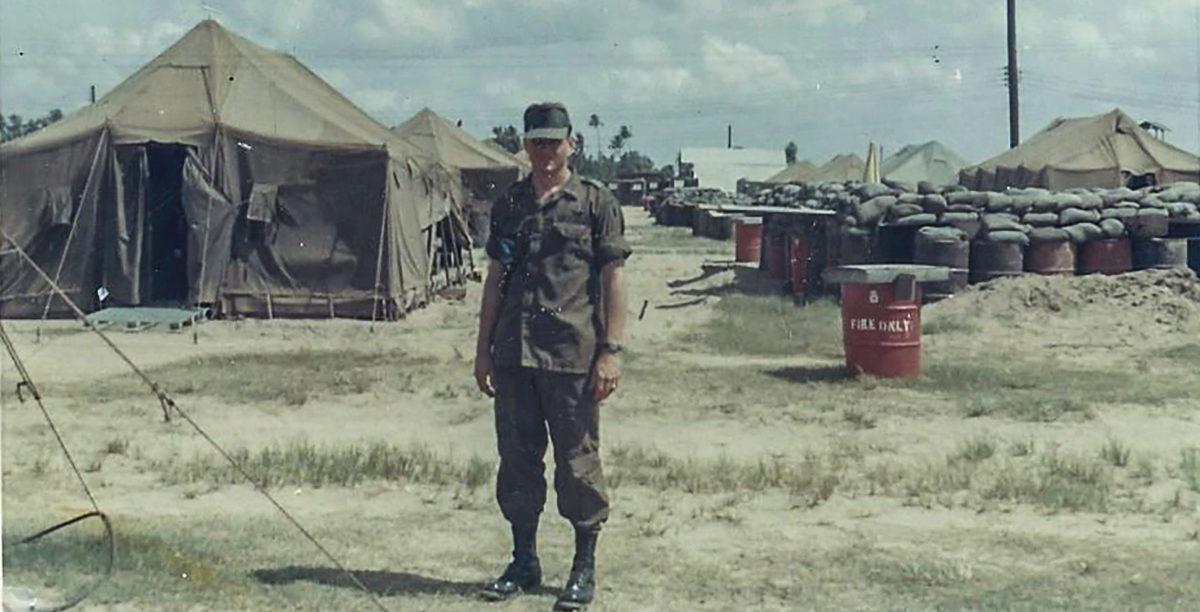

"When I was in Vietnam, I headed up a team that was assigned to support the Army of the Republic of Vietnam by flying in to the U Minh forest - one of the largest mangrove swamps in the south and a known Vietcong staging ground. To say this place was impenetrable is an understatement: in 1952, the French had sent in a battalion that was never heard from again. Five years after the war ended, there were still captives who had not escaped U Minh. It was that dark, that dangerous.

"So the situation was this: there were two captive soldiers in there, and we dropped in six Army SEALS to retrieve them. The minute those guys dropped, you could see smoke everywhere. 'Pop-pop-pop!' Shots fired everywhere. We were in there for two to three weeks, and we got to within 150 yards of those captives, but, after an American advisor was killed, we were pulled out. We never got our captive soldiers, and two of the SEALs were killed in our attempt."

"Leaving those men behind, we felt the mission had been a failure. But a few months later, the head of the SEAL team came to thank us personally for trying our best to get their guys out. That's when we got the rest of the story."

"There had been a new SEAL member in the crew that we dropped, and he'd broken some of the protocols that kept their team running smoothly. It all made sense, too: they had to have so much confidence in each other -- and they did have confidence in each other -- so when this one guy fell out of sync, it hurt the entire team."

"That really made the importance of strong teams sink in. Every member of a team plays a part, and all of the parts have to work seamlessly together for the entire team to succeed. As a leader, your job is to give every member a chance to do what they do best. If you overlook that, you are asking for failure."

5. "As usual, Guardian was perfect in all respects."

"Some version of this quote will be the title of my book - it's that important to me. It has nothing to do with me, personally, being 'perfect.' As the S-3 operations officer for the 13th Combat Aviation Battalion, I led a team whose area of operations was everything south and west of the Mekong River in South Vietnam. It was a dangerous time, as you can imagine, but we were determined. We went by the name "Guardians of the Mekong" and this quote was the greeting we received when we came back from our missions. It was engraved on a plaque that was given to me by my 13th CAB S-3 staff at my farewell party. In the decades since, it has become a source of motivation for me that I have shared with teammates, coaches, mentors, and superiors."

We're glad you are 'retiring' sir, because this is one book we want to read.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Grad Student Dan Schrage

circa 1974

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)